International action

In December 2016, in a resolution that expressed concern over “the continued flow of international recruits to ISIL [ISIS],” the UN Security Council introduced new legal obligations on all UN member states. Amongst these was a requirement for states to share biometric and biographic information about “foreign terrorist fighters and other individual terrorists and terrorist organizations” through “bilateral, regional and global law enforcement channels.” States were also obliged to provide that information to “national watch lists and multilateral screening databases.”

A follow-up resolution was approved a year later in which the Security Council returned to the question of watchlists. The 2017 resolution was more specific than its predecessor requiring states to:

…develop watch lists or databases of known and suspected terrorists, including foreign terrorist fighters, for use by law enforcement, border security, military, and intelligence agencies to screen travellers and conduct risk assessments and investigations…

The resolution also repeated the call to “share this information through bilateral and multilateral mechanisms” – with Interpol being the key example of the latter – and encouraged the provision of “capacity building and technical assistance by Member States and other relevant Organizations to Member States as they seek to implement this obligation.” A 2019 resolution called on states to address “linkages” between terrorists and organised crime groups, substantially widening the scope of this transnational security project.

Resolution 2322(2016)

Resolution 2396 (2017)

Resolution 2482 (2019)

Resolution 2322(2016)

Resolution 2396 (2017)

Resolution 2482 (2019)

From obligation to implementation

The obligations set out in the UN Security Council resolutions lack detail or practical advice on what exactly such watchlists should contain, how they should work, and how they should be maintained. Some clarity was offered in a UN document adopted in 2018, with further assistance coming from the Global Counter-Terrorism Forum (GCTF).

The GCTF was set up on the initiative of the USA in 2011 and describes itself as “an informal, apolitical, multilateral counterterrorism (CT) platform that contributes to the international architecture for addressing terrorism,” by providing a “platform for CT officials and practitioners around the world to share expertise and strategies and to develop widely applicable good practices and tools.” It “facilitates frank and open discussions among stakeholders” as part of its “anticipatory and nimble approach towards identifying and addressing emerging trends and its central commitment to support United Nations (UN) counterterrorism efforts.”

Members of the GCTF are able to launch issue-specific initiatives “to foster dialogue among stakeholders and/or to develop an outcome document.” The documents that result from these initiatives, often branded as “toolkits” or “good practices,” seek to inspire changes in national government policy and practice. They don’t have the binding force of law, but the production of norms in this manner avoids the lengthy bureaucratic wrangling of formal law-making whilst isolating state activity from public and democratic scrutiny and oversight.

In practice, the formal and informal spaces of international norm-setting on security and counter-terrorism are closely intertwined. For example, the UN Security Council’s 2017 resolution introducing legal obligations on states regarding watchlisting, biometrics and travel surveillance, approvingly cites the work of the GCTF. In 2018, the USA and Morocco partnered through the GCTF to launch an initiative on terrorist travel, which was launched “on the margins of the UN General Assembly.” The following year, the UN launched its own Countering Terrorist Travel initiative, part-funded by the USA and a host of other states. This sits alongside a host of others; 17 initiatives have been launched since 2015, with the USA a lead state in nine of those.

Global Counter Terrorism Forum initiatives since 2015

| Start | Initiative | Lead states (Partners) | End | Output |

| 2015 | Border Security Initiative | Morocco, USA | Good Practices in the Area of Border Security and Management in the Context of Counterterrorism and Stemming the Flow of Foreign Terrorist Fighters | |

| 2016 | Strategic Communications Initiative | Switzerland, UK | Zurich‐London Recommendations on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism and Terrorism Online | |

| 2016 | Soft Target Protection Initiative | Turkey, USA | Antalya Memorandum on the Protection of Soft Targets in a Counterterrorism Context | |

| 2017 | Nexus between Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism Initiative | Netherlands | 2018 | The Hague Good Practices on the Nexus between Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism |

| 2019 | Policy Toolkit with the view of operationalizing The Hague Good Practices. | |||

| 2017 | Initiative on Addressing the Challenge of Returning Families of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) | Netherlands, USA | 2018 | Good Practices on Addressing the Challenge of Returning Families of Foreign Terrorist Fighters (FTFs) |

| 2017 | Initiative to Address Homegrown Terrorism | Morocco, USA | 2018 | Rabat – Washington Good Practices on the Prevention, Detection, Intervention and Response to Homegrown Terrorism |

| 2018 | Initiative to Counter Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) Threats | Germany, USA | 2019 | Berlin Memorandum on Good Practices for Countering Terrorist Use of Unmanned Aerial Systems |

| 2018 | Initiative on Improving Capabilities for Detecting and Interdicting Terrorist Travel through Enhanced Terrorist Screening and Information Sharing | Morocco, USA | 2019 | New York Memorandum on Good Practices for Interdicting Terrorist Travel |

| 2019 | Initiative on National-Local Cooperation in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism | Indonesia, Australia | 2020 | Memorandum on Good Practices on Strengthening National-Local Cooperation in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism Conducive to Terrorism |

| 2019 | Initiative on Criminal Justice Responses to the Linkages Between Terrorism, Transnational Organized Crimes and International Crimes | Nigeria, Switzerland | 2020 | Addendum to The Hague Good Practices on the Nexus between Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism: Focus on Criminal Justice |

| 2021 | Memorandum on Criminal Justice Approaches to the Linkages between Terrorism and Core International Crimes, Sexual and Gender-based Violence Crimes, Human Trafficking, Migrant Smuggling, Slavery, and Crimes against Children | |||

| 2019 | Maritime Security and Terrorist Travel Initiative | USA (T.M.C. Asser Institute) | 2021 | Addendum to the GCTF New York Memorandum on Good Practices for Interdicting Terrorist Travel |

| 2019 | Watchlisting Guidance Manual Initiative | USA, the UN Office of Counter-Terrorism, UN Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate | 2021 | Counterterrorism Watchlisting Toolkit |

| 2020 | Ensuring Implementation of Countering the Financing of Terrorism Measures While Safeguarding Civic Space | Morocco, Netherlands, UN | 2021 | Good Practices Memorandum for the Implementation of Countering the Financing of Terrorism Measures While Safeguarding Civic Space |

| 2021 | Indonesia, Australia | 2022 | Gender and P/CVE Policy Toolkit | |

| 2021 | Awareness Raising & Operationalizing the GCTF “Racially or Ethnically Motivated Violent Extremism”* Toolkit Initiative | USA, Norway, CVE Working Group | 2022 | GCTF “REMVE” Toolkit |

| 2021 | Initiative on the Practical Use of the GCTF Memorandum on Good Practices on National-Local Cooperation in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism | Indonesia, Australia | 2022-23 | Workshops, mapping/gap analysis, “multi-stakeholder dialogues,” policy toolkit |

| 2021 | Initiative on Funding and Enabling Community-Level P/CVE: Challenges, Recommendations and Emerging Good Practices | Indonesia, Australia, (Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund, GCERF) | 2023 | Framework Document |

Through workshops with state officials, the GCTF Terrorist Travel Initiative developed a set of “good practices” designed to “reinforce how countries and organizations can use the border security tools prescribed in [Security Council Resolution] 2396 to stop terrorist travel.” The resulting document, known as the New York Memorandum, was approved by the GCTF at its ministerial meeting in September 2019. It notes that implementing the UN obligations regarding biometrics, watchlisting and travel data “can be complex, resource-intensive and expensive,” and so it provides “non-binding guidelines for good practices” to assist states.

At the same meeting, the USA and UN itself co-launched the Watchlisting Guidance Manual Initiative. Designed to build upon the New York Memorandum, it resulted in the production of a Counterterrorism Watchlisting Toolkit. The GCTF states that while the New York Memorandum “established good practices for policy makers to consider,” the Toolkit “helps countries implement these practices by providing nineteen recommendations for practitioners and frontline officials to consider when establishing and implementing a counterterrorism watchlist process.”

One commentary on the Toolkit notes that it “uncritically exports the flawed U.S. watchlisting system as a standard for the rest of the world to follow, without recognition of its serious problems.” US attempts to encourage other states around the world to converge with its security model are, of course, nothing new. Following the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the country went on a political and diplomatic offensive to encourage other states to pass a swathe of new laws and policies, including on issues – such as the surveillance and profiling of people travelling by air and by sea [links to API/PNR pieces] – that remain on the agenda today.

In particular, Guiding Principle 37a. See: UN Security Council Counter Terrorism Committee, ‘Security Council Guiding Principles on Foreign Terrorist Fighters: The 2015 Madrid Guiding Principles + 2018 Addendum’, S/2015/939 and S/2018/1177, https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ctc/sites/www.un.org.securitycouncil.ctc/files/files/documents/2021/Jan/security-council-guiding-principles-on-foreign-terrorist-fig.pdf

Resolution 2396(2017), p.4

Data from https://www.thegctf.org/

In particular, Guiding Principle 37a. See: UN Security Council Counter Terrorism Committee, ‘Security Council Guiding Principles on Foreign Terrorist Fighters: The 2015 Madrid Guiding Principles + 2018 Addendum’, S/2015/939 and S/2018/1177, https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ctc/sites/www.un.org.securitycouncil.ctc/files/files/documents/2021/Jan/security-council-guiding-principles-on-foreign-terrorist-fig.pdf

Resolution 2396(2017), p.4

Data from https://www.thegctf.org/

Turbo-charged watchlists

The type of watchlists encouraged by these laws, norms and initiatives can be seen as turbo-charged contemporary incarnations of the Gazette, though there are of course vast differences. While the Gazette was geared towards known criminals, contemporary watchlisting systems are supposed to include known and suspected terrorists, criminals, “national security threat actors,” and a host of others who do not fall into either of these two categories, but may still be of interest to the authorities.

The watchlists of the 18th, 19th and early 20th century were also reliant upon the issuance, circulation and storage of official identity documents, photographs and written descriptions of individuals. Contemporary watchlists retain this, but can also contain, interconnect and reference vast quantities of digitised information drawn from an ever-wider range of sources: travel reservations, identity document details, social media posts, financial information, reports from officials and informants, biometric data, and much more. The GCTF’s Watchlisting Toolkit calls on states to: “Strive for interoperability of systems across government agencies as permitted by national law,” so that users can “access various information systems to better complete their official roles.”

The scale of information available has led to the growing use of algorithmic and machine learning systems to identify individuals who may be of interest to the authorities, based on them matching certain traits, or falling within a particular category or population group. This aspect of the watchlisting infrastructure is rarely made clear in official documentation, though it is often hinted at – the UN’s guidance refers to “traveller risk assessment and screening procedures,” and the GCTF’s manual mentions “secure screening of travelers and travel documents, and… relevant risk assessments and information access.” The term “vetting” is also employed by officials to refer to automated screening and profiling techniques. [link to piece on ICAO]

Furthermore, the watchlisting infrastructure of the 21st century is not just distributed amongst different state agencies, but amongst different states. States will generally have one agency or entity with primary responsibility for assessing nominations from other agencies to their watchlist, and the GCTF’s Watchlisting Toolkit recommends that states integrate any existing systems into “a centralized watchlist or database.” However, the ability to share that information across borders with agencies in other jurisdictions means that multiple entities may have the opportunity not just to access data on individuals, but to gather and store information about them. The same individual could be on the watchlists of multiple states, with each of them possessing different types of information about the person in question. Any individual seeking to have that information corrected or deleted faces a difficult, if not impossible, challenge of clearing their name in multiple jurisdictions. [link to piece on redress]

In the context of the emerging transnational security architecture, the word “watchlist” does not describe a single list or system, but rather a sprawling and proliferating infrastructure that encompasses a whole host of different public and private actors cooperating within and between different states. This undoubtedly offers new possibilities for the detection and tracking of terrorists and criminals (amongst others), though it does nothing to address the underlying causes of terrorism and crime. It also offers new means of political repression and raises substantial challenges for upholding individual rights. As Fionnuala Ní Aoláin, a former UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms while Countering Terrorism, highlighted with regard to UN Security Council Resolution 2396:

Given the well-documented practices of multiple states in targeting civil society activists, writers, dissenters, and human rights defenders as terrorists the prospect of lists of this kind should provoke deep concern for the protection of rights. Here, Security Council dictate may be used by states to nefariously target those who disagree with them in new and highly coercive ways not only within their borders but… with co-operation and impunity across borders.

P.22

P.22

What’s in a watchlist?

Millions of entries

The amount of information accessible via any state’s watchlisting system is dependent on a wide variety of factors. The infrastructure developed by the US over the last two decades provides the most extensive case study, involving a daunting array of agencies, institutions and systems. The EU’s emerging watchlisting infrastructure provides a less sprawling example, though it remains in constant development. Official and press reports on the UK’s watchlisting system also offer some useful insights into the extent of that infrastructure.

In the US, the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) maintains a database called the Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE), which stores data on individuals known or believed to be connected with terrorism, as well as “transnational organised crime actors” and “individuals detained during military operations who do not meet the international definition of ‘prisoner of war’.” It holds both classified and unclassified biometric, biographic and other data and, as of October 2020, it contained entries for “about 2.5 million people.” Almost all of them were foreign nationals not permanently residing in the US, raising important issues regarding their ability to access redress and remedies. [link to redress piece]

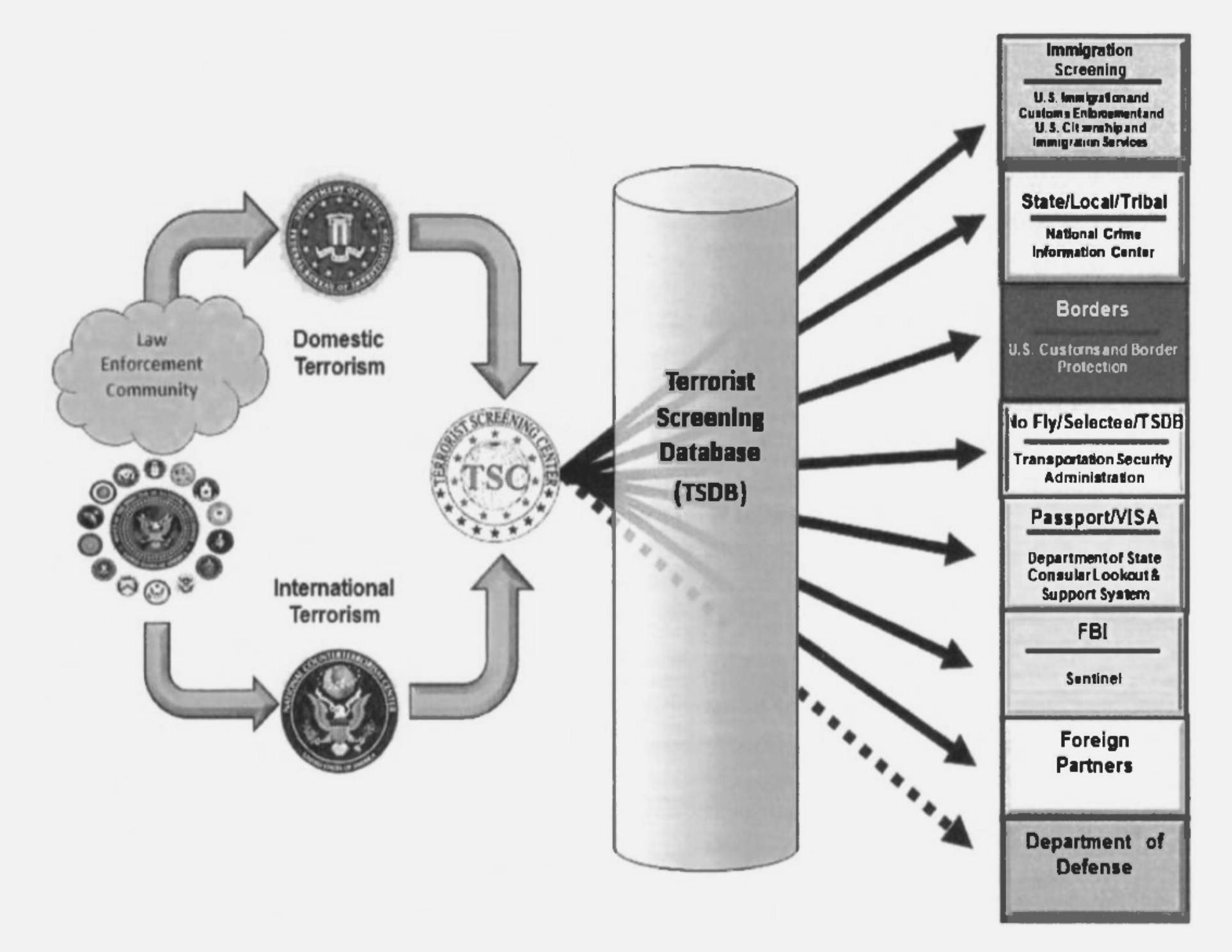

Subsets of information from TIDE are distributed to the Terrorist Screening Center (TSC), which is hosted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Those subsets make up a database that is now called the Threat Screening System, and previously as the Terrorist Screening Database (TSDB). It is also referred to simply as the terrorism watchlist. Like the TIDE, the watchlist has also grown substantially over the years. In 2008, it contained “approximately” one million records on 400,000 individuals. As of June 2016, the NCTC said there were “approximately one million person records” in the system. More recent figures are not available, but if the NCTC’s 2016 statement refers to the number of individuals recorded in the system (rather than simply the number of records), then it grew in size by 250% in eight years.

[infographic/visual to make things clearer?]

While TIDE is the primary source for the US terrorist watchlist, there are other systems with a watchlisting function. As has been documented by the Surveillance Resistance Lab, the IDENT database maintained by the Department for Homeland Security is being transformed into a “next-wave biometric database that will vastly expand its surveillance capabilities and supercharge the deportation system,” at a cost of at least $6 billion. Files in the database may include biometrics, social media data, location data, car numberplates, and more. According to a DHS presentation available online, an “IDENT watchlist” holds data on 4.7 million people, including “Known and Suspected Terrorists”, “Deported Felons”, “Aliens with a Criminal History” and “Visa Denials”, amongst others. As detailed below (see ‘Building a biometric cloud for the world’), it is this system that the DHS is aiming to interconnect with other databases around the world as part of its Biometric Data Sharing Partnership program

The watchlist maintained by the Terrorist Screening Center is used to generate further datasets, of which perhaps the best known is the No Fly List. Individuals placed on this list are prohibited from flying to, from or over the US. In January 2023, a version of the list dating from 2019 was discovered by a Swiss hacker on a publicly-available server operated by an airline company. It contains some 1.5 million entries – a figure far larger than any other that has ever been publicly-cited regarding the No Fly List – and while it is unclear how many unique individuals these entries refer to, it is evidently a huge number of people. An analysis of the dataset carried out by the Council on American-Islamic Relations estimated that “more than 1.47 million of those entries regard Muslims – over 98 percent of the total,” confirming longstanding accusations of anti-Muslim bias in the US watchlisting infrastructure.

The EU has maintained a common form of watchlist since the 1990s, when the Schengen Information System (SIS) came into operation. The SIS stores millions of alerts on people and objects of interest to the authorities for one reason or another, including those who should be denied entry to the Schengen area on national security grounds, and those who should be subject to “discreet or specific checks” or questioning. At the end of 2022, it contained more than one million alerts on people, of whom more than 561,000 were subject to an entry ban (whether for national security or other reasons, such as having violated immigration law); and more than 160,000 flagged for “discreet or specific checks.” Hundreds of different agencies and authorities have access to the system, though they cannot all necessarily access all categories of alert.

The forthcoming European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) will also include a separate watchlist, to store:

…data related to persons who are suspected of having committed or taken part in a terrorist offence or other serious criminal offence or persons regarding whom there are factual indications or reasonable grounds, based on an overall assessment of the person, to believe that they will commit a terrorist offence or other serious criminal offence.

Initially aimed at those obliged to apply for a “travel authorisation” – that is, anyone who does not currently need a visa to travel the EU – the ETIAS watchlist was subsequently extended to cover people applying for short and long-stay visas, as well as residence permits. The need for such a watchlist has never been made clear to the public: the legal proposal to establish ETIAS was not accompanied by an impact assessment, contrary to the European Commission’s own guidelines, and the explanatory memorandum to the proposal offers no explanation. Its potential size remains unknown. Technical decisions on its development that might reveal such information have not been published.

Transnational organised crime actors are individuals “known or suspected to be or have been engaged in conduct constituting, in aid of, or related to transnational organized crime, hereby posing a possible threat to national security, and do not otherwise satisfy the requirements for inclusion in the TSDB as KSTs.”

National Counterterrorism Center, ‘Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE)’, October 2020, https://www.dni.gov/files/NCTC/documents/news_documents/TIDE_Fact_Sheet_Oct2020.pdf

“The Terrorist Screening Center maintains the Threat Screening System (formerly known as the Terrorist Screening Database) to serve as the U.S. Government’s consolidated watchlist for terrorism screening information.” See: United States Government Accountability Office, Counterterrorism: Action Needed to Further Develop the Information Sharing Environment’, June 2023, p.35, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105310.pdf

Rick Kopel, Principal Deputy Director, Terrorist Screening Center, ‘Statement Before the House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation Security and Infrastructure Protection’, 9 September 2008, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/news/testimony/the-terrorist-screening-database-and-watchlisting-process

Joint response from the NCTC and FBI, undated, https://www.feinstein.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/f/b/fb745343-1dbb-4802-a866-cfdfa300a5ad/BCD664419E5B375C638A0F250B37DCB2.nctc-tsc-numbers-to-congress-06172016-nctc-tsc-final.pdf

The Congressional Research Service has noted: “in 2014 only about 8% of the TSDB identities—around 64,000—were on the No Fly List, and about 3%—roughly 24,000—were on the Selectee List.” See: Jerome P. Bjelopera, Bart Elias and Alison Siskin, ‘The Terrorist Screening Database and Preventing Terrorist Travel’, Congressional Research Service, 7 November 2016, p.8, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/terror/R44678.pdf

David Covucci and Mikael Thalen, ‘U.S. airline accidentally exposes ‘No Fly List’ on unsecured server’, 19 January 2023, https://www.dailydot.com/debug/no-fly-list-us-tsa-unprotected-server-commuteair/

NCTC Guidance

Article 34, Regulation (EU) 2018/1240, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R1240

Ref COM implementing decisions

Transnational organised crime actors are individuals “known or suspected to be or have been engaged in conduct constituting, in aid of, or related to transnational organized crime, hereby posing a possible threat to national security, and do not otherwise satisfy the requirements for inclusion in the TSDB as KSTs.”

National Counterterrorism Center, ‘Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE)’, October 2020, https://www.dni.gov/files/NCTC/documents/news_documents/TIDE_Fact_Sheet_Oct2020.pdf

“The Terrorist Screening Center maintains the Threat Screening System (formerly known as the Terrorist Screening Database) to serve as the U.S. Government’s consolidated watchlist for terrorism screening information.” See: United States Government Accountability Office, Counterterrorism: Action Needed to Further Develop the Information Sharing Environment’, June 2023, p.35, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105310.pdf

Rick Kopel, Principal Deputy Director, Terrorist Screening Center, ‘Statement Before the House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Transportation Security and Infrastructure Protection’, 9 September 2008, https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/news/testimony/the-terrorist-screening-database-and-watchlisting-process

Joint response from the NCTC and FBI, undated, https://www.feinstein.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/f/b/fb745343-1dbb-4802-a866-cfdfa300a5ad/BCD664419E5B375C638A0F250B37DCB2.nctc-tsc-numbers-to-congress-06172016-nctc-tsc-final.pdf

The Congressional Research Service has noted: “in 2014 only about 8% of the TSDB identities—around 64,000—were on the No Fly List, and about 3%—roughly 24,000—were on the Selectee List.” See: Jerome P. Bjelopera, Bart Elias and Alison Siskin, ‘The Terrorist Screening Database and Preventing Terrorist Travel’, Congressional Research Service, 7 November 2016, p.8, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/terror/R44678.pdf

David Covucci and Mikael Thalen, ‘U.S. airline accidentally exposes ‘No Fly List’ on unsecured server’, 19 January 2023, https://www.dailydot.com/debug/no-fly-list-us-tsa-unprotected-server-commuteair/

NCTC Guidance

Article 34, Regulation (EU) 2018/1240, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R1240

Ref COM implementing decisions

Data categories and data sources

A single biometric or a last name combined with either a first name, date of birth, passport number or “unique identifying numbers such as alien registration numbers, visa numbers and social security numbers” is considered sufficient for making an entry in the US Terrorist Screening Database, provided that there is also information to support the “reasonable suspicion” criteria. However, there is an extensive set of other information that can be included in an individual’s file: contact details, place of birth, occupation, employer and educational background, amongst other things.

The range of sources from which data can be gathered is vast. An internal document produced by the National Counterterrorism Center in 2013, classified as SECRET, refers to the following:

- data from visas retrieved from the State Department’s Consular Consolidated Database;

- biometrics including facial images, fingerprints, iris scans, handwriting, signatures, scars/marks/tattoos and DNA gathered from agencies including the Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, FBI and the State Department, via driving licence authorities in at least 16 US states, and from “foreign partners”;

- “clandestinely collected travel data,” received from the CIA;

- biometric and biographic data on detained KSTs (“known and suspected terrorists”) obtained via CIA HUMINT (human intelligence) sources;

- “clandestinely acquired foreign government information from the CIA’s Hydra program,” for example through vetting Pakistani nationals listed in TIDE against Pakistani passports and providing “TIDE record enhancement information (biographic and biometric identifiers) back to DTI [the Counterterrorism Center’s Directorate of Terrorist Identities]”;

- information from Interpol red notices;

- “additional data fusion points” received from the National Media Exploitation Center, tasked with sifting through documents, video, audio and other media for intelligence purposes; and

- Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act “classified cables”.

Bilateral agreements on the exchange of “terrorism screening information” provide one way in which information is received from and shared with “foreign partners.” Research for this project, based on publicly-available information, indicates that the US has at least 45 such agreements in place; a 2019 US court judgement states that “TSDB data is… shared with more than sixty foreign governments.” The true number may be higher, as such exchanges may take place informally or on the basis of memoranda of understanding or other agreements that are not made public. Indeed, the number of agreements referred to here includes those that are legally required for participation in the US Visa Waiver Programme, but the majority of those have not been made public. In 2019, a group of US politicians raised concerns over the US’ information-sharing agreements, referring to sworn testimony from an FBI official which indicated the agency “has never stopped disseminating watchlist information to a foreign government as a result of that government’s human rights abuses.”

Whatever the precise number of these agreements and whichever states they have been signed with, many of them have been in place for quite some time. In 2003, George W. Bush approved Homeland Security Presidential Directive 6 (HSPD-6), which mandated the establishment of “an organization [the Terrorist Screening Center] to consolidate the Government’s approach to terrorism screening and provide for the appropriate and lawful use of Terrorist Information in screening processes.” The same Directive also gave the green light to enhanced information-sharing with foreign states, requiring that the US Secretary of State develop a proposal “for enhancing cooperation with certain foreign governments, beginning with those countries for which the United States has waived visa requirements, to establish appropriate access to terrorism screening information of the participating governments.”

[graphic/visualisation: USA’s data-sharing agreements]

The agreements that are accessible to the public generally govern the exchange of three types of information. According to the agreement between the USA and Georgia, the two parties should exchange:

- Terrorist screening information: “identity information/personal data, such as name, date of birth, passport number or other identity document number(s), or citizenship/nationality regarding known or suspected terrorists,” as well as “special category of data,” which is undefined;

- Background information: “additional information beyond Terrorist Screening Information which may include location of Encounter, watchlist status, or whether the individual is considered armed or dangerous”

- Derogatory information: “intelligence or information that demonstrates the nature of an individual’s association with terrorism or terrorist activities”

Some agreements also refer to “correcting information” – that which is “intended to correct a misidentification of a person as a known or suspected terrorist or any other error in data provided under this Agreement,” according to the agreement with Slovenia. Through these agreements, both parties agree to provide one another with terrorist screening information on individuals posing “a threat to the national security” of the US and the other signatory state, as well as on those who “pose a threat to the national security of other countries.”

One of the countries with which the USA certainly has some form of terrorist screening information arrangement is the UK, although there is no public record of any such deal. The UK of course has its own watchlisting infrastructure, made up of a number of different systems that are in the process of being, or have recently been, upgraded. One, known as the Warnings Index, has been described as: “A database of names available to Border Force of those with previous immigration history, those of interest to detection staff, police or matters of national security.” It is due to be replaced by a “strategic watchlist capability” known as Helios, which itself will be integrated into a new border data system called Border Crossing.

An official report revealed that the “Watchlist Information Control Unit imports data for this watchlist from around 30 sources.” The names of only two of those sources – “fraud prevention company GB Group and data analytics firm, Dun & Bradstreet” – have become public. A Home Office team associated with the Warnings Index has been reported to hold “data on more than 650 million people, including children under the age of 13.” That includes “information about people’s ethnicity, immigration status, nationality, criminal record history, and biometrics.” The UK also operates a system called Semaphore, used to receive and analyse data on “advance passenger data provided by companies transporting people across the border.”

In the EU, alerts in the SIS can contain a wide variety of data such as names, date of birth, photographs and biometrics, physical description, nationality and potential behaviour (e.g. violent, suicide risk), amongst other things. They must be entered by authorities of EU member states, though policing agency Europol can propose to member states that they enter alerts. Those concerning entry bans for national security purposes, or for “discreet or specific checks,” are most likely to be entered at the behest of law enforcement or intelligence agencies. Europol also has a role in circulating information provided by non-EU states on potential foreign terrorist fighters that may be included in the SIS. As an official document setting out that process noted: “Much of the information on non-European FTFs is held by third countries.” The agency’s ability to process information from third states – in particular, biometric data – has recently been extended.

Entries in the EU’s ETIAS watchlist, meanwhile, will be composed of a more limited set of data, made up of “one or more” of ten biographic data categories:

- surname;

- surname at birth;

- date of birth;

- other names (alias(es), artistic name(s), usual name(s));

- travel document(s) (type, number and country of issuance of the travel document(s));

- home address;

- email address:

- phone number;

- the name, email address, mailing address, phone number of a firm or organisation;

- IP address.

However, this data is merely that which is to be used for comparisons with travel authorisation and visa applications. Equally, the data included in the SIS is unlikely to be all that is known about an individual. Lying behind it may be a far broader range of information, stored in the databases of member state police forces, intelligence agencies or Europol. In the future, it may also be combined with a range of other data sources as part of the push being spearheaded by EU agencies to develop a system of “travel intelligence.”

Europol describes “travel intelligence” as encompassing “PNR [Passenger Name Record], EES [the EU Entry/Exit System], ETIAS, VIS [the EU Visa Information System] and other relevant information management initiatives on the movements of persons and goods.” A report produced by Europol and Frontex proposed a “European System for Traveller Screening” that would use automated data correlation, database checks and “European and national risk profiles” to generate individual risk profiles for each traveller. It appears that steps towards this system are being taken through Europol’s efforts to develop a “European Travel Intelligence Centre,” which may also involve data collection from unspecified “private partners.”

Furthermore, at the beginning of 2023, Europol began working with the DHS on a “Pilot Program on systematic CT [counter-terrorism]-Related Information Exchange.” Documents released under EU transparency rules say that information previously exchanged between Europol and the DHS was “essentially lists of suspects with CT links.” The Pilot Program was to begin with DHS providing Europol with “Electronic System of Travel Authorization applications denied on national security grounds.” The documents note that if the project was successful, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection would be pleased to provide a similar service to the EU in analyzing denied applications to the European Travel Information and Authorization System, once it is operational and is appropriate.” They go on to say that if the project were deemed a success after six months, “we can jointly agree to expand the scope of the program to cover also other CT-related data sets of mutual interest.” It is through projects such as these that an increasingly-integrated transnational security architecture is being developed.

NCTC guidance, pp.30-32

Trenga judgment

‘Rep. Ilhan Omar, Members of Congress send a letter to Secretary Mike Pompeo to Protect American Citizens from Human Rights Abuses Abroad’, 28 June 2019, https://omar.house.gov/media/press-releases/rep-ilhan-omar-members-congress-send-letter-secretary-mike-pompeo-protect

‘Homeland Security Presidential Directive/Hspd-6’, 16 September 2003, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nspd/hspd-6.html

These are set out in Article 34(4) of the ETIAS Regulation:

NCTC guidance, pp.30-32

Trenga judgment

‘Rep. Ilhan Omar, Members of Congress send a letter to Secretary Mike Pompeo to Protect American Citizens from Human Rights Abuses Abroad’, 28 June 2019, https://omar.house.gov/media/press-releases/rep-ilhan-omar-members-congress-send-letter-secretary-mike-pompeo-protect

‘Homeland Security Presidential Directive/Hspd-6’, 16 September 2003, https://irp.fas.org/offdocs/nspd/hspd-6.html

These are set out in Article 34(4) of the ETIAS Regulation:

Being listed

“A virtual prison”

There are many ways for an individual to end up on a watchlist: following court proceedings; as part of a police investigation; through the provision of information by informants; through the hoovering up of open-source information from the press or social media; or through information provided by a foreign government. Whilst watchlists are ostensibly targeted at terrorists and criminals, there are multiple cases of people being wrongly listed due to their religion, beliefs or simply having the same name as someone under suspicion. Some people believe they have been placed on the US watchlist for refusing to become an informant for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), as in the case of Aswad Khan:

Khan had been an international student attending Northeastern University in Boston to study business management. In 2011, after graduating, he returned to the U.S. on a visitor visa. While staying with family, he was approached by the FBI with an offer to become a paid informant for the bureau. Khan declined. After leaving the country a few weeks later, Khan and his legal team believe he was placed on the U.S.’s no-fly list as well as the terrorist watchlist.

This has not just affected Khan himself, but also his friends, family and even people with whom he has only a vague connection:

After that fateful FBI visit, many of Khan’s contacts who traveled to the U.S. started to be repeatedly detained at the U.S. border, sometimes for hours. Those stopped included friends and acquaintances in Pakistan, as well as people with whom he was only casually connected on social media. A consistent feature of the stops, something that at least five of Khan’s contacts confirmed, is that they were asked about their relationship with him at the border. The contacts said U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers suggested to them during interrogations that Khan was a dangerous person, a possible terrorist. The officials made it clear that he was the source of their problems at the border.

Khan told The Intercept:

It’s like I’m in a virtual prison being on this list. The FBI has all this power over you. They own your life. They’re the gatekeepers of your prison, even though you haven’t done anything wrong to justify being put in there.

It should be noted that the government has refused to confirm to Khan whether or not he is on any such list, with one of his lawyers only able to say they believe “it is very likely.” The lack of information given to affected individuals is one of the many problems raised by the US system of watchlisting, [link to redress piece] and Khan’s case is far from being an isolated one. Multiple other cases of wrongful inclusion on the watchlists – in particular, the No Fly list – have been documented, with devastating consequences. As highlighted by the American Civil Liberties Union a decade ago:

Being placed on a U.S. government watchlist can mean an inability to travel by air orsea; invasive screening at airports; denial of a U.S. visa or permission to enter to the United States; anddetention and questioning by U.S. or foreign authorities—to say nothing of shame, fear, uncertainty,and denigration as a terrorism suspect. Watchlisting can prevent disabled military veterans fromobtaining needed benefits, separate family members for months or years, ruin employment prospects,and isolate an individual from friends and associates.

Watchlisting systems can also be used for overtly political purposes. The German government, in its resolute support for the Israeli government, recently banned former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis from entering the country to speak at a Palestinian solidarity event. The British-Palestinian surgeon Ghassan Abu Sitta was prevented from speaking at the same event and was subjected to “a Schengen-wide ban on his entry into Europe,” according to what French officials told him when they barred him from entering the country at a Paris airport. This was later overturned following a legal challenge.

Nick Wing, 7 Ways That You (Yes, You) Could End Up On A Terrorist Watch List, Huffpost, 25 July 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/terrorist-watch-list_n_5617599

Nick Wing, 7 Ways That You (Yes, You) Could End Up On A Terrorist Watch List, Huffpost, 25 July 2014, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/terrorist-watch-list_n_5617599

Broad criteria

In the US, guidance produced by the National Counter-Terrorism Center in 2013 and leaked by The Intercept set out the official policies and procedures for watchlisting an individual. Regardless of the way information on an individual is obtained, the document says the official assessing a nomination to the watchlist should have “reasonable suspicion” that they are a “known or suspected terrorist.” The entity that makes the nomination is known as a “nominator.” According to the guidance:

To meet the REASONABLE SUSPICION standard, the NOMINATOR, based on the totality of the circumstances, must rely upon articulable intelligence or information which, taken together with rational inferences from those facts, reasonably warrants a determination that an individual is known or suspected to be or has been knowingly engaged in conduct constituting, in preparation for, in aid of, or related to TERRORISM and/or TERRORIST ACTIVITIES. There must be an objective factual basis for the NOMINATOR to believe that the individual is a KNOWN or SUSPECTED TERRORIST. Mere guesses or hunches are not sufficient to constitute a REASONABLE SUSPICION that an individual is a KNOWN or SUSPECTED TERRORIST. Reporting of suspicious activity alone that does not meet the REASONABLE SUSPICION standard set forth herein is not a sufficient basis to watchlist an individual. The facts, however, given fair consideration, should sensibly lead to the conclusion that an individual is, or has, engaged in TERRORISM and/or TERRORIST ACTIVITIES.”

There is extensive further discussion of what precisely reasonable suspicion entails. The document says that “irrefutable evidence or concrete facts are not necessary,” but that “to be reasonable, suspicion should be as clear and as fully developed as circumstances permit.” The standard is deliberately “lower than that required for a criminal conviction (i.e., beyond a reasonable doubt)” – one aim of the US watchlisting system is to keep tabs on individuals considered potentially risky, but against whom there are not necessarily grounds for criminal prosecution. This approach is reflected in the GCTF Watchlisting Toolkit, which calls for states to set out:

…multiple threat categories within the centralized watchlist. Not all individuals on the watchlist represent the same terrorist threat to national security. States should consider the threat posed by an individual as identified through collected information.

The scope of the US watchlisting system, already broad, was expanded under the Trump administration through a March 2019 Executive Order. As well as dealing with “known and suspected terrorists,” the Department of Homeland Security says it now has official approval for the watchlisting of “national security threat actors” – though this term is nowhere to be found in the Executive Order.

The DHS nevertheless takes it to encompass “transnational organised crime actors,” and “individuals detained during military operations who do not meet the international definition of ‘prisoner of war’.” The DHS noted that the addition of these two new groups “significantly changes the nature of the information” it would receive from the TSC. The new practices also reflect a UN Security Council resolution that expanded UN member states’ watchlisting obligations to encompass suspected criminals as well as terrorists.

According to the 2013 guidance, nominations to the US watchlist can also be made for “immigration and visa screening” purposes even where the reasonable suspicion standard is not met. “In instances where REASONABLE SUSPICION is not found, NOMINATORS should also determine whether the individual should be nominated to support immigration and visa screening,” says the document. This may be the case when the individual in question is the spouse of a known or suspected terrorist; their child; or considered to be an endorser, espouser, supporter or inciter of terrorism, amongst other things.

In the EU, no such guidance with the same level of detail has been made public, and the legal framework for the SIS delegates the criteria for entering alerts to national law. However, as noted above, this will also soon be accompanied by the new ETIAS watchlist, which will include data on:

…persons who are suspected of having committed or taken part in a terrorist offence or other serious criminal offence or persons regarding whom there are factual indications or reasonable grounds, based on an overall assessment of the person, to believe that they will commit a terrorist offence or other serious criminal offence.

This definition provides substantial scope for data collection. There is no clarity as to what “suspected” means, nor any further explanation of the terms “factual indications”, “reasonable grounds”, or “overall assessment of the person,” with the latter phrase reading as an invite to gather as much information as possible on individuals. While the EU prides itself on having the strongest legal framework for data protection in the world, it is also firmly anchored to a security model that requires the collection, processing and sharing of vast quantities of personal data. There has long been a tension between these two points, and that tension is likely to become sharper as this watchlist, and other associated elements of the EU’s security architecture, develop.

NCTC guidance, p.13

NCTC guidance, p.34

P.17

Transnational organised crime actors are individuals “known or suspected to be or have been engaged in conduct constituting, in aid of, or related to transnational organized crime, hereby posing a possible threat to national security, and do not otherwise satisfy the requirements for inclusion in the TSDB [Terrorist Screening Database] as KSTs.” See: Privacy Impact Assessment for the Watchlist Service, July 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-dhsall027d-watchlistservice-july2020.pdf

NCTC 2013 watchlisting guidance, p.42

NCTC guidance, p.13

NCTC guidance, p.34

P.17

Transnational organised crime actors are individuals “known or suspected to be or have been engaged in conduct constituting, in aid of, or related to transnational organized crime, hereby posing a possible threat to national security, and do not otherwise satisfy the requirements for inclusion in the TSDB [Terrorist Screening Database] as KSTs.” See: Privacy Impact Assessment for the Watchlist Service, July 2020, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-dhsall027d-watchlistservice-july2020.pdf

NCTC 2013 watchlisting guidance, p.42

Using a watchlist

State watchlists are primarily intended to detect convicted, suspected or ‘potential’ terrorists and criminals during border control checks, although they may also be made available to law enforcement or other agencies agencies operating elsewhere and used for other purposes. UN Security Council resolution 2396(2017) includes an obligation for member states to set up “watch lists or databases of known and suspected terrorists, including foreign terrorist fighters,” which should be used by “law enforcement, border security, customs, military, and intelligence agencies to screen travelers and conduct risk assessments and investigations”. It goes on to encourage states “to share this information through bilateral and multilateral mechanisms.”

The GCTF’s Watchlisting Toolkit offers a similarly broad understanding of when and how watchlists should be used, saying that “an integrated national counterterrorism watchlist… should be accessible to all relevant law enforcement and border authorities, in particular in areas where watchlist users, such as screeners, interface with the public.” The document goes on to suggest ways in different users may be granted different access rights: “border management and customs may use the watchlist to screen travelers, while law enforcement agencies may use the watchlist to conduct risk assessments or during encounters.”

Thus, while border controls and immigration procedures are the primary way in which watchlists are employed, they are far from being the only ones. Examining how they function in this context offers clues as to how they may be deployed in other areas, and how watchlist data can be shared with and accessed by other states, particularly as the spread of digital technologies facilitates simpler and swifter access to data. A comparison can be drawn with the way in which the UK’s “hostile environment” for undocumented migrants is being extended: legal obligations for companies and institutions to check peoples’ immigration papers is facilitated through digital technologies, making immigration checks by landlords, employers, banks and others swifter and easier. It is entirely feasible to imagine the same thing happening with requirements to vet individuals for associations to terrorism or other security threats via extending access to national and international watchlisting infrastructure.

P.8, GCTF Watchlisting Toolkit

P.21, GCTF Watchlisting Toolkit

P.8, GCTF Watchlisting Toolkit

P.21, GCTF Watchlisting Toolkit

Border and immigration controls

It is the potential mobility of foreign terrorist fighters across state borders without detection that animated the push to further develop the transnational security architecture from 2014 onwards, and those borders are perceived as ideal sites for the interdiction of potential security threats. This does not just concern checks upon arrival at a border itself, but a whole system of vetting and screening of would-be migrants and travellers. As noted above, visa and immigration screening is a key purpose of the US watchlist. Similarly, in the EU, the ETIAS watchlist will be used alongside databases such as the SIS to screen applicants for travel authorisations, short and long-stay visas, and residence permits.

In the case of international travel, particularly by air, this screening process begins prior to a travellers’ departure. A would-be traveller may have to submit a request for a travel authorisation or a visa, a process which will feed the applicants details’ through a series of database checks and algorithmic assessments designed to flag individuals whose details match those in law enforcement alerts, or who match any screening rules put in place – for example, with regard to gender, place of residence, or age.

All travellers, meanwhile – whether they require a visa or travel authorisation or not – will have data from their identity document and travel booking transmitted to states that require the transmission of Advance Passenger Information and/or Passenger Name Record data. These rules are being put in place in an increasing number of states due to international legal obligations, and are expanding from airlines [link to air travel piece] to boats [link to maritime travel piece]. will also receive a range of personal data prior to the vessel’s departure, and (usually) once again after it has left, allowing for a similar series of checks. This data, in particular PNR data, is frequently used for automated profiling and the algorithmic assessment of individuals’ travel patterns, companions and means of payment, amongst other things. Depending on the results of these checks, the individual in question may be prevented from boarding the vessel, held for search and questioning, or be allowed to pass (with or without officials making a discreet note of their belongings, travel companions, and so on).

In the US, Customs and Border Protection (an agency of the Department of Homeland Security) operates the Automated Targeting System (ATS) to screen passengers travelling to or from the US, making use of various “risk-based assessments” and “targeting rules” to try to identify previously-unknown individuals:

ATS compares information about individuals travelling on flights to or from the U.S. against U.S. law enforcement databases as well as redress records and travel history of the passengers. It compares existing information about individuals entering and exiting the country with patterns of known illicit activities (“targeting rules”) identified through risk-based assessments and intelligence. It flags possible matches to these targeting rules. It allows users to search data to provide a consolidated view of data about a person or entity of interest. It also provides users with a consolidated view of data about a person entering or departing the U.S. so a decision about their admissibility can be rendered. As such, it allows DHS to focus law enforcement attention on those individuals most likely to pose a risk while facilitating the entry of the overwhelming majority of legitimate travellers by reducing inspection requirements.

This is similar to the way in which the EU’s Passenger Name Record systems work. Each member state operates a Passenger Information Unit, which can “process PNR data against pre-determined criteria.” As detailed elsewhere in this research [link to ICAO piece], the only reason for authorities to collect and use PNR data is for “datamining and profiling by means of these records, linked to other major datasets (such as bulk communications data, or bulk financial transaction data)… full PNR data are simply not needed for any other, normal, legitimate law enforcement or border control purpose.”

The EU’s police and border control agencies would like to build upon these systems to develop something more akin to that used by the US. As noted above, Europol and Frontex have put forth plans for a “European System for Traveller Screening” that would utilise:

…a person-centric data management approach to ensure that database checks and risk assessment are done in the best possible way with all relevant data about the individual being accessible and visible for prompt decision making.

The idea is for this to integrate a broad range of EU and national data sources and to employ algorithmic profiling systems for assigning a “risk score” to each individual:

Border management should also rely on automated targeting or screening systems for performing risk management on the travellers with advance information. It would be beneficial, from an operational perspective and for the purpose of assessing the risk of the individual traveller, if the targeting system were to include not only API, PNR, and Visa or ETIAS application data, and if the risk management were to include combinations of these data. The experiences of border authorities outside the EU have demonstrated the operational added value of this.This would require legislative changes and most likely the use of AI to combine those sources effectively. [emphasis added]

Digital technologies make it increasingly easy for the border to follow individuals. Mobile devices make it possible for officials to check an individual’s immigration status by scanning their fingerprint or face, and transmitting the image to a central database for checks. These practices are already widespread in both the US and the EU, and immigration and law enforcement authorities are being equipped with an increasing number of mobile devices that can be connected to an ever-broader range of information. The immigration control function of watchlists can thus extend far beyond the border itself: into other countries, in the case of pre-travel vetting and screening; and into states’ own territories, through the use of mobile identification devices.

In the USA, “travel authorisations” are issued through the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA), while in the EU this will be done through the European Travel Information and Authorisation System. Similar systems and procedures exist for processing visa applications.

Cross reference pieces on API and PNR

This type of observation is what is required, for example, under EU legislation dealing with ‘Alerts on persons and objects for discreet checks, inquiry checks or specific checks’, Regulation (EU) 2018/1862, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R1862#d1e2843-56-1

In the USA, “travel authorisations” are issued through the Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA), while in the EU this will be done through the European Travel Information and Authorisation System. Similar systems and procedures exist for processing visa applications.

Cross reference pieces on API and PNR

This type of observation is what is required, for example, under EU legislation dealing with ‘Alerts on persons and objects for discreet checks, inquiry checks or specific checks’, Regulation (EU) 2018/1862, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018R1862#d1e2843-56-1

Extending access

There are also multiple other ways and places in which watchlists can be deployed. In the US, the No Fly list and other related lists (the Selectee and Expanded Selectee List) are distributed by the TSC to the Transport Security Administration for use in the Secure Flight program, which also covers domestic air travel. Secure Flight is just one of seven DHS “component systems” that receive watchlist data in one form or another, and it can also be accessed by the Department of Defense, the FBI, and “federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial law enforcement.”

A 2019 court judgment noted that the watchlist was made available to “18,000 state, local, county, city, university and college, tribal and federal law enforcement agencies and approximately 533 private entities for law enforcement purposes.” Amongst those “private entities” are private railway police forces; educational institutions; hospitals; prisons and probation services; information technology, fingerprint database and forensic science service providers; and animal welfare organizations.

The broader the access to the watchlist, the more frequently it will have an impact on individuals. As documented by the American Civil Liberties Union, this means that even fairly routine encounters with local law enforcement agencies will reveal the fact that an individual is listed:

When a Denver man who was a member of [a] gun rights group subsequently had a fender-bender [car crash], a routine police check of the National Crime Information Center database showed that the man was listed as a member of a terrorist organization, even though his record had previously been expunged from the Denver database after a lawsuit brought under the Freedom of Information Act.

The fact of being listed can also make encounters with law enforcement agencies more likely:

Francisco Martinez, a civil rights lawyer and activist in the Chicano movement, was stopped by local law enforcement in multiple states because he had been watchlisted, despite having been cleared of terrorism-related charges decades earlier. The federal government paid Martinez over $100,000 in 2007 to settle lawsuits arising out of the stops.

There are echoes here of the case of John Catt, a British pensioner who regularly attended peaceful protests outside a weapons factory in Britain, where he sketched the demonstrations. Catt and his daughter Linda were both placed on the police’s National Domestic Extremism Database and had their activities monitored for years. Information stored about them included the numberplate of Catt’s car – meaning that every time he passed an Automatic Numberplate Recognition camera an alert was triggered, saying that the vehicle was “of interest to public order unit, Sussex police.” It took Catt years, and a case at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, to have his records expunged.

As discussed above, the US has dozens of agreements with states around the world to facilitate the sharing of “terrorism screening information”. When the US administration first started promoting these in the early-to-mid 2000s, US officials went on a charm offensive, offering states access to portions of the TSDB in order to demonstrate its utility. The diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks includes one from the US embassy in London noting that “UK law enforcement agencies are using the ‘No Fly List’ to detain and interview individuals who may pose a threat to U.S. interests.” The TSC also “shared relevant portions of the TSDB” with the German police, who checked more than 147,000 names against it as part of the security vetting for the 2006 World Cup. The cable reported that “there were no ‘hits’.” New Zealand also expressed interest in gaining access to the No Fly List, which the embassy in Wellington saw as “further evidence that the New Zealand government would be receptive to participation in the HSPD-6 pilot project on terrorist lookout information sharing.”

The cables contain dozens of other examples of these types of reports, and make clear the extensive efforts that take place behind closed doors to encourage US “partners” to participate in its security infrastructure. Beyond the signing of agreements on the exchange of data, those efforts include the provision of hardware and software designed to facilitate the receipt and transmission of information between the US, partner states, and international organisations such as Interpol.

[PISCES/MIDAS infographic/visuals]

The Personal Identification Secure Comparison and Evaluation System (PISCES) is a system that US official say “deploys cutting edge technology that allows border control officials to screen travelers against terrorism databases in 23 countries.” This suggests that any country using the system is able to run searches against databases in any other country using the system, including the US’ own systems. The US is currently aiming to “expand and improve PISCES,” according to 2021 testimony by a State Department official, by providing it to more countries and by improving integration “with DHS and international organization watchlisting and biometrics technology and programs, and to incorporate emerging technologies to defeat increasingly sophisticated efforts by terrorist networks to travel.” There is no further detail on what precisely this entails.

The testimony goes on to say that in Somalia and Guinea, PISCES has been integrated with a separate border control system developed and provided by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), a former intergovernmental body that became a UN “related organisation” in 2016. That system, MIDAS (Migration Information and Data Analysis System), is described by the IOM as “a high-quality, user-friendly and fully customizable Border Management Information System (BMIS) for States in need of a cost-effective and comprehensive solution.” It can be connected to other national and international systems (such as those hosted by Interpol), and allows the creation of “reports according to the types of traveller data needed, such as country of origin, age, gender, travel purpose or whether the person has been detected in an Alert List.” In 2018, 20 countries were using the system. Research for this project indicates that it is now in place at the borders of more than 50 states.

Data from the watchlist is distributed to the TSA’s Office of Transportation Threat Assessment and Credentialing, and the Secure Flight program; to the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Passenger Systems Program Office, US Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT), for inclusion in the huge IDENT biometric database, and the Automated Targeting System; to the Office of Intelligence & Analysis; Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); and the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Fraud Detection and National Security Data System (FDNS-DS).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Data from the watchlist is distributed to the TSA’s Office of Transportation Threat Assessment and Credentialing, and the Secure Flight program; to the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Passenger Systems Program Office, US Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT), for inclusion in the huge IDENT biometric database, and the Automated Targeting System; to the Office of Intelligence & Analysis; Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); and the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Fraud Detection and National Security Data System (FDNS-DS).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Building a biometric cloud for the world

The International Biometric Information Sharing (IBIS) program, launched in 2022 by the DHS, introduces some further novel elements to US attempts to mould and expand global watchlisting infrastructure. The purpose of IBIS is to improve the ability of DHS and its “foreign partners” to “establish more definitively the identity and assess eligibility of an individual presenting for an immigration benefit or when encountered by DHS law enforcement in border and immigration related contexts.”

That is, it aims to use border controls and other immigration-related “encounters” (for example, immigration raids) to ensure that individuals are vetted by having their identities checked against the vast biometric identity infrastructure maintained by the DHS:

IBIS facilitates fingerprint-based bilateral biometric and biographic information sharing between the United States and a foreign partner. IBIS enables the automatic comparison of the fingerprints collected by DHS or a foreign partner on border crossers, suspected criminals, asylum seekers, irregular migrants, refugees, and other individuals encountered by government representatives against U.S. and partner country terrorism, national security, identity, immigration and criminal records.

This is intended to identify those who “present a threat to the security or welfare of the United States, identify perpetrators of identity fraud in the immigration process, and enhance the vetting of individual travellers.” This, in turn, will reduce “likelihood of onward travel to the [US] by national security threat actors, criminals, and undocumented individuals,” whilst promoting “the integrity of global travel and migratory systems” In return for obtaining access to DHS databanks, foreign governments are encouraged to share biometric and other data with DHS and other US agencies. This is due to become an obligation under the US Visa Waiver Program, and has been discussed frequently by EU institutions and member states since they were notified of it in 2022.

One facet of the IBIS program is the Biometric Data Sharing Partnership (BDSP) model. Through this, some states will simply use DHS databases as if they were their own. In short, the DHS is aiming to build a “cloud” of biometric and other data that will be expanded and tapped into by the DHS and other US agencis, as well “partners” across the globe.

According to the DHS, there are two key novelties of the BSDP model compared to existing agreements and programmes. Firstly, data-harvesting: partner states “permit DHS to retain all biometric enrolments” that they have undertaken “regardless of a match to an existing DHS record.” In short: DHS keeps all the data that is compared against its records. The second novelty is the possibility of foreign states storing data they collect in DHS systems, rather than their own. A DHS privacy impact assessment notes that US foreign assistance funds may be used to build biometric systems in other countries. In such a scenario, “that partner’s biometric system uses IDENT/HART as its data repository for biometric matching purposes.” Under this model, “all biometric and associated biographic information obtained by the partner for relevant purposes… will be enrolled in IDENT/HART. DHS will not query a partner fingerprint database but will instead query the enrolled partner holdings retained in IDENT/HART.”

A number of reasons are given to justify this plan. There is “the reality that BDSP partners typically do not have the technical bandwidth and capabilities to respond to the volume of searches DHS would need to conduct of their databases.” According to this argument, simple technical expediency makes the program necessary. The USA could, of course, use its foreign assistance funds to provide “BDSP partners” with the “technical bandwidth and capabilities” needed to meet DHS requirements. However, such an approach would not offer the USA the degree of power and leverage over partner states, or the same level of access to information, that building a centralised biometric cloud for the world does.

The DHS also argues that the collection and retention of vast amounts of biometric and biographic data from states around the world is in fact beneficial from a privacy and data protection standpoint, as it “minimizes the number of times DHS exchanges personally identifiable information with foreign partners.” While it does indeed minimise the number of data exchanges, it also places data under the control of the US authorities, and thus gives the individuals affected few – if any – privacy protections or means of redress.

‘Privacy Impact Assessment for the DHS International Biometric Information Sharing Program (IBIS) – Biometric Data Sharing Partnerships (BDSP)’, DHS/ALL/PIA-095(a), 18 November 2022, p.2

Ibid.

Ibid

Ibid., p.4

‘Privacy Impact Assessment for the DHS International Biometric Information Sharing Program (IBIS) – Biometric Data Sharing Partnerships (BDSP)’, DHS/ALL/PIA-095(a), 18 November 2022, p.2

Ibid.

Ibid

Ibid., p.4